Why do so many people refuse to accept that the theory of evolution could possibly be true? No doubt some really do believe that the account of the creation of the living world given in the Bible is literally true, though it is hard to understand why they do. The origin stories of a Middle Eastern tribe of over two thousand years ago seem a rather shaky foundation for a world view at the present time.

I would imagine that more people just dislike the idea of kinship with other animals. In fact they would reject that last sentence - human beings are not animals, they are something superior, whether touched by some divinity or not. Something very human is to devise some rational seeming argument to justify a firmly held belief. A common one in this area is often expressed as, "If we evolved from monkeys, how come there are still monkeys?" It doesn't take very deep thought to find the flaw in that argument. Evolution is likely to come about when some members of a species find themselves in changed circumstances from before: if the climate gets colder, some monkeys in a high mountain valley may be cut off in suddenly very cold conditions. They might all die out, but maybe some have genes which give them thicker fur or some other factor for better survival, so that they leave descendants while the others die. After some generations there may be a new species, related to the original monkeys but no longer the same. But populations of the original monkeys may still be living happily in areas where the climate change was not so drastic. There is no reason at all why an entire species has to evolve into another one.

If evolution is the reason for the diversity of the living world, it is hardly surprising that different species share a good many genes. If humans were unique, it would be surprising, though not impossible, for them to have genes in common with the - I mustn't say other - animals. This was brought home to me rather vividly a few years ago, when I had a skin allergy problem, and was prescribed a cream to relieve the irritation. A while later one of our cats also developed a skin problem, and received precisely the same cream from the vet. That hardly surprised me as an evolutionist - after all, mammals in general should have plenty of features in common. But it should give anti-evolutionists a puzzle to solve, if they are really willing to think things through. Maybe God was economical in His wonders? And of course those of us with mammalian pets at least, cats and dogs, will know how much we and they have in common psychologically - affection, jealousy, anger and sulkiness at least are easily recognisable in them.

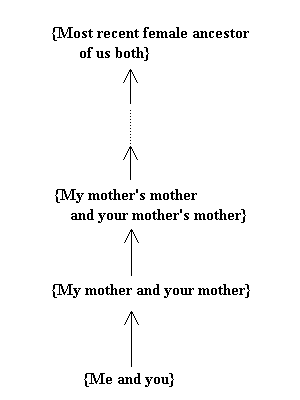

Nobody should have any objection to the following illustration:

|

It shows various collections of individuals, or "sets", to use the mathematical term. The lowest one contains two individuals, me and you. According to mathematical custom, the names of the members of the set are enclosed by curly brackets. An arrow points up to the next set, containing my mother and your mother. Another arrow takes us up to the set containing our maternal grandmothers, that is, our mothers' mothers. The dots indicate that the sets continue on to mothers' mothers' mothers and so on and on. Each set will contain two members until finally we reach one containing just the most recent female ancestor that we both have in common. The previous set of course must contain two sisters. |

Of course the number of sets, or generations, that we have to pass over before reaching that common ancestor depend on how closely related we are. If we are natives of the same region or country, it might just be a few generations. If we come from far separated parts of the world, we might have to go back quite a number of generations before reaching that ancestor. But not necessarily - none of us know every detail of our family history, and some people travelled far, even a few centuries ago. There was a Viking outpost on the coast of what is now Canada a thousand years ago or so, and at least one Amerindian woman travelled to Iceland and left descendants, of whom some eighty are still around - see this archaeologica.org news item. So clearly some Icelanders and some native Americans would find a common female ancestor after just a few generations. By the way, just for the sake of accuracy, the glacier in Iceland is called "Vatnajökull" and the name of the geneticist involved is Carlos Lalueza-Fox. Both names have got a little garbled on the web page.

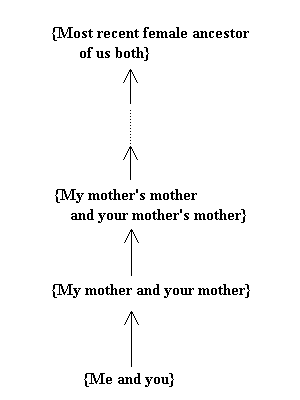

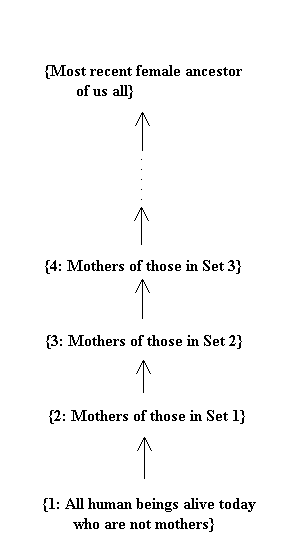

Given that, then it's just a fairly short step to this picture:

|

Again it illustrates a number of sets, this time owing their inspiration to Daniel C. Dennett's splendid book on evolution,

Darwin's Dangerous Idea (Simon and Schuster 1995, Penguin Books 1996). This time the membership of the lowest set,

labelled "1", is more complicated to describe: "all human beings alive today who are not mothers". The complication is

there just in order that Set 2, "mothers of those in Set 1", should not have any members in common with Set 1, which can cause

difficulties in the argument. If you want more details, you can check Dennett's correction of the

errors which he and others discovered in the original edition of the book.

Anyway, with a Set 2 of mothers, we go on not surprisingly to a Set 3 of mothers of mothers and so on and on. The sets will tend to become smaller in size as we go back through the generations - many women will have more than one daughter who herself goes on to become a mother. But it is possible for the sets to stay the same size, of course, if every woman in Set X has just one daughter who becomes a mother and thus joins set (X - 1). There may be other daughters, but they die young or for some other reason remain childless. That kind of stasis over a generation or two is obviously more likely when the sets are small. Nevertheless we must surely in the end reach a set of one member: the most recent female ancestor of all us humans. That argument is hardly more controversial than the previous one about your mother and mine. Note that the argument does not show that our most recent female ancestor belonged to our own species homo sapiens - she might have been one of a related ancestral species. Actually biological evidence shows that she was one of us, and most probably lived in Africa around 150,000 years ago - surprisingly recently, in fact. But I don't want to pursue these matters further here, fascinating though they are: there is an excellent Wikipedia article which you can refer to for up-to-date information on the woman known as Mitochondrial Eve. |

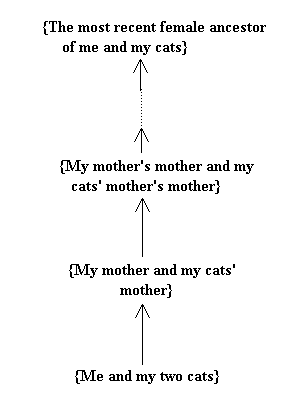

But now to my last set diagram, which might even shock a few evolutionists, who have never thought of things in this direct way:

|

This time the lowest set has three members, me and my two cats - well, I say "my" for short, though they are claimed by the whole

human household of which I am a member. Anyway, they are sisters, and so had the same mother, meaning that the next set up has two members,

my mother and their mother. On we go with maternal grandmothers and so on - but this time of course the membership of each set is going to

remain at two for a tremendous number of generations. Notice that it's generations and not time directly - clearly cat generations are a

whole lot shorter than human ones. Nevertheless, at some point, given the truth of evolution, we must reach a set with one member, the most

recent female ancestor of me and my cats. It seems that according to current palaeontological evidence, that ancestor was most likely an

Epitherian, some early mammal living in Late

Cretaceous times, some 90 million years ago or so.

Even if the details about Epitheria are wrong, the set argument has to be correct, doesn't it, given evolution? Maybe some people never think about it so personally! |

Well I certainly do. Whenever a cat of mine is prescribed the same medicine, or sulks because I refuse to give her a lick of my cheese, or pats my nose gently with her paw to get permission to join me under my warm duvet on a winter night, or rubs noses with me in greeting when I come home, then I wonder, "What did our great-great ... well, very large number but certainly finite number of greats ... grandmother look like?"